251204.Understanding-the-compositions-interior-structure-evolution-and-formation-of-giant

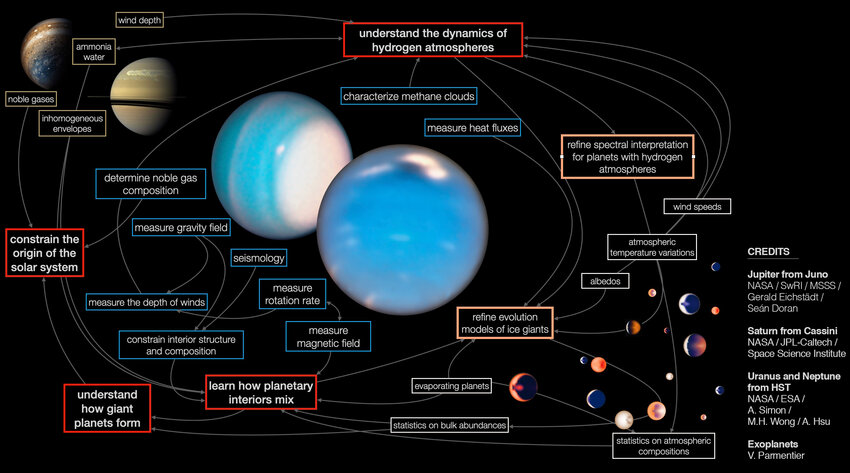

Understanding the compositions, interior structure, evolution and formation of giant planets requires information from many different sources. The exploration of Uranus and Neptune provides essential pieces of that puzzle, bridging a gap between gas giants Jupiter and Saturn and exoplanets. Credits: Creative Commons Attribution 4.0 International.

Stefan Pelletier

Abstract

Measuring the atmospheric composition of exoplanets and relating this to planet formation is a long-standing goal of the planetary science community.

However, this task requires inferring abundances for the major elements from which planets form – a notoriously difficult task.

Even for Jupiter and Saturn, we only have a handful of measurements, mainly due to their freezing cold temperatures causing most elements to rain out of the observable atmosphere where they become impossible to measure.

This leaves a critical piece of the puzzle still missing in our understanding of what giant planets are made of and how they formed. With temperatures exceeding 2000K, ultra-hot Jupiters offer a unique opportunity to directly determine the full chemical inventory of giant planets.

Specifically, even rock-forming elements that would otherwise be impossible to measure on colder planets (e.g., Fe, Mg, Si) are vapourised, becoming accessible via remote sensing.

This means that we can measure refractory-to-volatile abundance ratios on ultra-hot Jupiters, which tell us the relative amounts of rocks and ices that are accreted when giant planets form – something that remains largely unconstrained even for the gas giants in our Solar System.

The caveat is that even for ultra-hot giant planets with exceedingly high dayside temperatures, their colder permanent nightsides are often still cold enough to form clouds that remove certain chemical species from the gas phase (effectively hiding them), making the inference of their bulk atmospheric abundances more difficult.

I will present my efforts in using a variety of ground-based high-resolution spectrographs and JWST to observe and characterise the atmospheres of ultra-hot giant exoplanets, with the goal of measuring their elemental compositions to try to link this back to their formation history.